Headspace 101 for .303's

Several generations of American shooters have been convinced by bad information that something mysterious and scary called "headspace" should be checked and re-checked on almost any surplus rifle, especially Lee-Enfields. The truth is less interesting but still worth knowing.

Stripped to its essentials, with a rimmed cartridge like the .303, headspace is simply the distance between the front of the bolt and the back of the barrel. It's the space where the "head" (rim) of the cartridge fits when the rifle is loaded.

Since there has to be some room to allow for varying rim thickness, the headspace is normally a bit more than necessary - giving what I call "head clearance", a little extra space so the bolt can close easily, even on the thickest rim allowed.

In addition, Lee-Enfields and their ammo were often made with a fair amount of space for dirt, mud, snow and other battlefield debris between the chamber and the cartridge's body and shoulder ("Body/shoulder clearance"). Since the cartridge is controlled by its rim, this clearance doesn't do any harm (except to handloaders who insist on full-length sizing).

When a full-power .303 cartridge is fired, a whole string of events occurs.

1. The firing pin shoves the case forward, rim against the breech.

2. The primer detonates. If it's not heavily crimped in place, it backs out, shoving the bolt and barrel as far apart as it can.

3. The thin, forward part of the case expands to fill and grip the chamber while the bullet moves out of the case and down the barrel.

4. The solid case head can't expand and grip the chamber, so it moves rearward, re-seating the primer, stretching the case walls just forward of the head, and stopping when it hits the bolt face. (In rear-locking actions like the Lee, the bolt and receiver also compress/stretch to add a little more movement. The higher the pressure, the more they move.)

5. If (and only if) the amount of head movement exceeds the elastic limits of the case, the cartridge separates into two pieces.

New cartridge cases can normally stretch a lot before breaking. Even with a minimum rim .054" thick and maximum "field" headspace of .074", the resultant .020" head clearance is well within the limits of new brass and it's very unlikely a new case will separate even if the headspace is somewhat more than the field maximum (which is pretty rare).

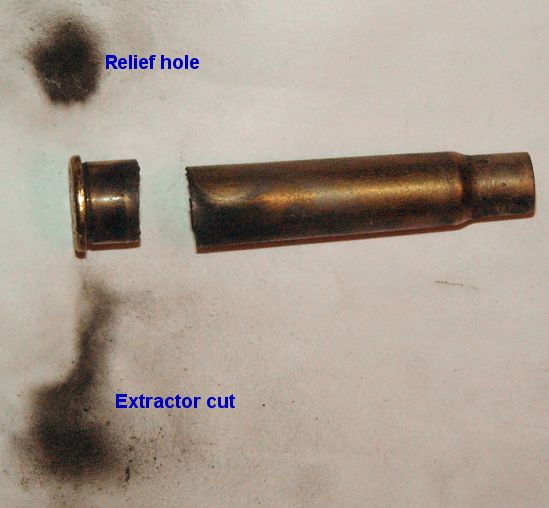

OK, but if one does separate I'm in deep trouble, right? Not really. It seems the short "cup" left behind the break is pretty good at keeping most of the gas where it belongs. Here's a demonstration -

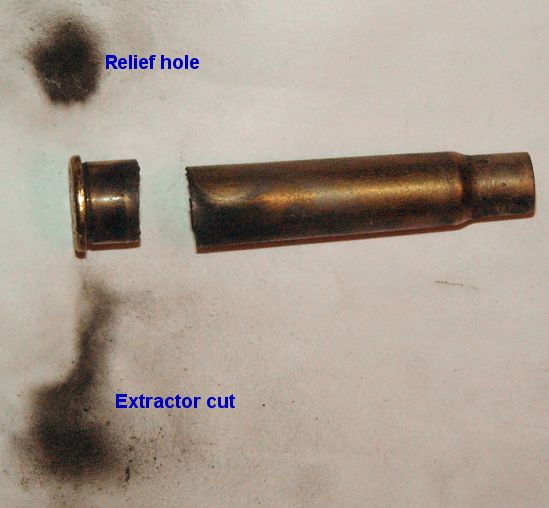

First I took a case that had been reloaded with heavy loads enough times so it was stretched near breaking.

I loaded it with a 180-grain bullet and 40 grains of 4895 - a reasonably stiff charge about 2 grains under "maximum" - and fired it in a much-abused Savage No.4 with a clean sheet of typing paper wrapped around the receiver.

When I opened the bolt, the separated head extracted. (The front piece of the case fell out when I happened to turn the rifle muzzle-up while removing the paper.)

The sooty paper shows where some gas escaped. No rips or holes, just a little soot - and only where the bolt meets the barrel. Had I been shooting from the shoulder and wearing glasses, I probably wouldn't have noticed the leak at all.

The point of all this is that excess headspace, even a bit beyond normal limits, isn't the terrible danger we've heard so much about. It's not a good thing for consistent ignition or long case life (although handloaders who neck-size or adjust F.L. dies carefully can control this) - but it's not a disaster waiting to happen.

Unless you're consistently getting broken cases when firing new ammo or brass, there's not much reason to be worried about headspace in these sturdy old Lee-Enfields. Relax and enjoy!

Handloading

If you handload for a .303 with generous headspace, there's no need to mess with bolt heads - changing the rifle's clearances to yield longer case life. You can control head clearance simply by changing technique.

When you fire a new case for the first time, use an improvised spacer ahead of the rim - anything from a precision metal washer to dental floss can work to hold the the cartridge head firmly against the bolt face and eliminate or reduce stretch even if head clearance is significant. Another way of accomplishing the same end is to use a bullet seated out far enough to jam into the lands, "headspacing" on the bullet instead of the case. Such techniques are useful only if the rifle has excess headspace. With normal headspace, initial stretch isn't enough to worry about.

After you've fire-formed your new cases they will fill the chamber fully, stopping on the shoulder just like a rimless cartridge. If you neck size, you'll have zero "headspace". If you have to full length size, adjust the die so the cases chamber with just a bit of resistance in the last few degrees of bolt rotation.

Finally, don't try to turn a .303 into a magnum. Keep the pressures below the limit and you reduce the small amount the bolt and receiver compress/stretch on firing in a rear-locking action.

With these techniques you can make your .303 cases last for dozens of loading cycles, even if your "gauge headspace" is well beyond the .074" field spec.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

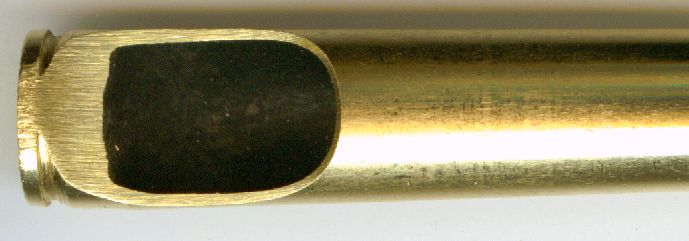

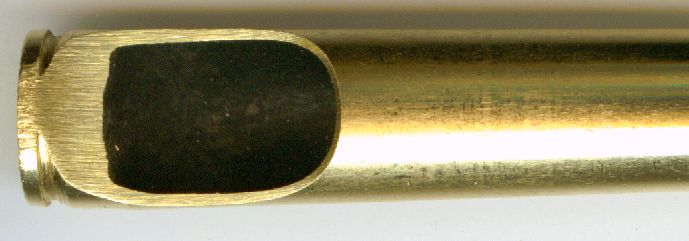

To demonstrate how we can control head clearance using only the shoulder, I filed off the rim of a once-fired Remington .303 case. After adding an extractor groove to fit a Mauser-size shellholder, I neck-sized, reloaded and fired this case 19 more times.

The load was a 180-grain jacketed soft-point over a lightly-compressed charge of IMR 4350 (giving an average velocity of 2310 fps for the 19 shots and listed at just under 39,000 CUP in my IMR data booklet). The test rifle was a 1943 Lithgow S.M.L.E. Mk.III*. 20 shots was enough for a practical test, I sectioned the case to examine the web/body junction area where thinning normally occurs.

This case, fired 19 times with no rim, has not stretched or thinned at all. I'm sure it could have continued for at least another 20 of these moderate loads.

It's clear to me that the .303's shoulder, alone without help from the normal rim, is entirely adequate to maintain "headspace" when sized in a way that preserves the shoulder location. Those handloaders who experience poor case life with neck-sized handloads should look for other factors to explain premature case failures. The most likely source of trouble is high pressure. More pressure means more action flex and that means shorter case life.

************************************************** ************************************************

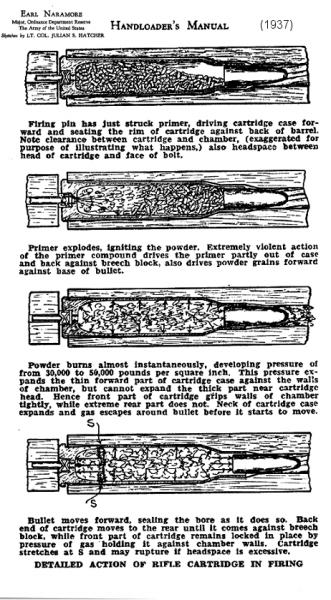

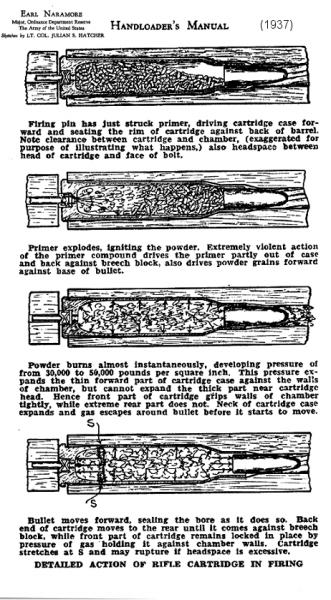

Just to demonstrate that there's nothing new (except computer animation), here's a page from a 1937 book I found online several years after first posting "Headspace 101 . . ."

Several generations of American shooters have been convinced by bad information that something mysterious and scary called "headspace" should be checked and re-checked on almost any surplus rifle, especially Lee-Enfields. The truth is less interesting but still worth knowing.

Stripped to its essentials, with a rimmed cartridge like the .303, headspace is simply the distance between the front of the bolt and the back of the barrel. It's the space where the "head" (rim) of the cartridge fits when the rifle is loaded.

Since there has to be some room to allow for varying rim thickness, the headspace is normally a bit more than necessary - giving what I call "head clearance", a little extra space so the bolt can close easily, even on the thickest rim allowed.

In addition, Lee-Enfields and their ammo were often made with a fair amount of space for dirt, mud, snow and other battlefield debris between the chamber and the cartridge's body and shoulder ("Body/shoulder clearance"). Since the cartridge is controlled by its rim, this clearance doesn't do any harm (except to handloaders who insist on full-length sizing).

When a full-power .303 cartridge is fired, a whole string of events occurs.

1. The firing pin shoves the case forward, rim against the breech.

2. The primer detonates. If it's not heavily crimped in place, it backs out, shoving the bolt and barrel as far apart as it can.

3. The thin, forward part of the case expands to fill and grip the chamber while the bullet moves out of the case and down the barrel.

4. The solid case head can't expand and grip the chamber, so it moves rearward, re-seating the primer, stretching the case walls just forward of the head, and stopping when it hits the bolt face. (In rear-locking actions like the Lee, the bolt and receiver also compress/stretch to add a little more movement. The higher the pressure, the more they move.)

5. If (and only if) the amount of head movement exceeds the elastic limits of the case, the cartridge separates into two pieces.

New cartridge cases can normally stretch a lot before breaking. Even with a minimum rim .054" thick and maximum "field" headspace of .074", the resultant .020" head clearance is well within the limits of new brass and it's very unlikely a new case will separate even if the headspace is somewhat more than the field maximum (which is pretty rare).

OK, but if one does separate I'm in deep trouble, right? Not really. It seems the short "cup" left behind the break is pretty good at keeping most of the gas where it belongs. Here's a demonstration -

First I took a case that had been reloaded with heavy loads enough times so it was stretched near breaking.

I loaded it with a 180-grain bullet and 40 grains of 4895 - a reasonably stiff charge about 2 grains under "maximum" - and fired it in a much-abused Savage No.4 with a clean sheet of typing paper wrapped around the receiver.

When I opened the bolt, the separated head extracted. (The front piece of the case fell out when I happened to turn the rifle muzzle-up while removing the paper.)

The sooty paper shows where some gas escaped. No rips or holes, just a little soot - and only where the bolt meets the barrel. Had I been shooting from the shoulder and wearing glasses, I probably wouldn't have noticed the leak at all.

The point of all this is that excess headspace, even a bit beyond normal limits, isn't the terrible danger we've heard so much about. It's not a good thing for consistent ignition or long case life (although handloaders who neck-size or adjust F.L. dies carefully can control this) - but it's not a disaster waiting to happen.

Unless you're consistently getting broken cases when firing new ammo or brass, there's not much reason to be worried about headspace in these sturdy old Lee-Enfields. Relax and enjoy!

Handloading

If you handload for a .303 with generous headspace, there's no need to mess with bolt heads - changing the rifle's clearances to yield longer case life. You can control head clearance simply by changing technique.

When you fire a new case for the first time, use an improvised spacer ahead of the rim - anything from a precision metal washer to dental floss can work to hold the the cartridge head firmly against the bolt face and eliminate or reduce stretch even if head clearance is significant. Another way of accomplishing the same end is to use a bullet seated out far enough to jam into the lands, "headspacing" on the bullet instead of the case. Such techniques are useful only if the rifle has excess headspace. With normal headspace, initial stretch isn't enough to worry about.

After you've fire-formed your new cases they will fill the chamber fully, stopping on the shoulder just like a rimless cartridge. If you neck size, you'll have zero "headspace". If you have to full length size, adjust the die so the cases chamber with just a bit of resistance in the last few degrees of bolt rotation.

Finally, don't try to turn a .303 into a magnum. Keep the pressures below the limit and you reduce the small amount the bolt and receiver compress/stretch on firing in a rear-locking action.

With these techniques you can make your .303 cases last for dozens of loading cycles, even if your "gauge headspace" is well beyond the .074" field spec.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

To demonstrate how we can control head clearance using only the shoulder, I filed off the rim of a once-fired Remington .303 case. After adding an extractor groove to fit a Mauser-size shellholder, I neck-sized, reloaded and fired this case 19 more times.

The load was a 180-grain jacketed soft-point over a lightly-compressed charge of IMR 4350 (giving an average velocity of 2310 fps for the 19 shots and listed at just under 39,000 CUP in my IMR data booklet). The test rifle was a 1943 Lithgow S.M.L.E. Mk.III*. 20 shots was enough for a practical test, I sectioned the case to examine the web/body junction area where thinning normally occurs.

This case, fired 19 times with no rim, has not stretched or thinned at all. I'm sure it could have continued for at least another 20 of these moderate loads.

It's clear to me that the .303's shoulder, alone without help from the normal rim, is entirely adequate to maintain "headspace" when sized in a way that preserves the shoulder location. Those handloaders who experience poor case life with neck-sized handloads should look for other factors to explain premature case failures. The most likely source of trouble is high pressure. More pressure means more action flex and that means shorter case life.

************************************************** ************************************************

Just to demonstrate that there's nothing new (except computer animation), here's a page from a 1937 book I found online several years after first posting "Headspace 101 . . ."

Author: Eric "Parashooter" (click here)

Collector's Comments and Feedback:

Reply

Reply

Countries

Countries Categories

Categories