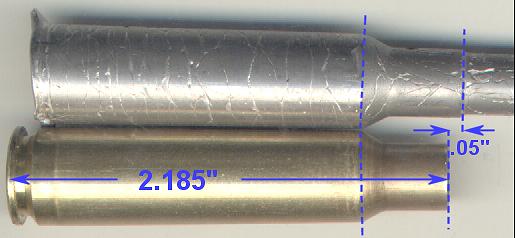

Bolt thrust (no friction) is frequently calculated on the inside diameter of the case at the web (since this is the only portion of the base 'touched' by internal pressure). For the .223 Rem. with an OD of .378" and walls .020" thick, we have an ID about .338", radius .169", area .0897". At the proof pressure cited, this would give 6990 lbs. of thrust (remember, no friction). That's as close as I can get to Ed's numbers using the old πr² business. Much depends on what one considers to be the effective thrust area - and there appears to be considerable disagreement, with some using the OD and others the ID at different points.

Of course, using the calculated area x pressure as a bolt-thrust figure fails to take any case/chamber friction into account. If there were perfect adhesion and no case stretch, bolt thrust would be zero - except where the primer backed out. (That's what we look for in the .22 Jet revolver, by the way. Any lube present and the cylinder locks up.) In actual practice we don't see perfect adhesion and we normally see some case stretching in medium rifle cartridges at pressures above ~30,000 psi, which should give us "dry" thrust numbers somewhere between zero and the calculated no-friction result.

The introduction of the "Tin Can" business to a topic trying to deal with bolt thrust at normal pressure is a distraction. The problem in 1921 was excessive chamber pressure, not increased bolt thrust at normal pressure.

The FA tests reported in Culver's "Tin Can" article and also in Hatcher's Notebook, Ch.XIV, were conducted on the 1920 NM ammo with plain cupronickel jacket, not the tin-plated 1921 ammo. Commenting on the 1921 ammo, greased, Hatcher wrote, ". . . if the bullet had been dipped in grease, this generally meant that the neck of the cartridge was greasy too. The space between the neck of the case and the neck of the chamber was filled with an incompressible substance, and the the first moderate rise in pressure found it impossible to expand the neck and release the bullet. Thus the powder was strongly confined right at the beginning of its ignition, and accordingly the pressure rose disastrously." ("Hydraulic lock" is the term I use, perhaps incorrectly.)

Although "cold-soldering" and consequent high bullet-pull with the tin-plated 1921 ammo seem to have contributed to the problem, Hatcher states that without grease, the neck expanded at initial pressure to release the bullet. He seemed to think the thick grease had a crucial role in raising chamber pressure. It probably depends on the type and amount of grease, as well as the fit of the case and chamber. One example of a partially-lubricated cartridge for modern rifle use is the SwissGP11, which for many years carried a thick ring of waxy sealer/lubricant at the junction of bullet and case, with no apparent problems. The Swiss chamber, however, is made about 1mm longer than the cartridge case, very possibly to provide a reservoir and/or escape route for the lube/sealer.

- Knowledge Library

- MKL Entry of the Month

- Australia

- Austro-Hungarian Empire

- Canada

- Czechoslovakia

- Denmark

- Finland

- France/Belgium

- Germany

- Italy

- Japan

- Norway

- Russia

- South America

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Turkey

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Yugoslavia

- Is my rifle authentic or a fake?

- Jay Currah's Lee Enfield Web Site

- On-line Service Records (Canada)

- Technical Articles/Research

- Forum

- Classifieds

- What's New?

-

Photo Gallery

- Photo Gallery Options

- Photo Gallery Home

- Search Photo Gallery List

-

Photo Gallery Search

- Video Club

- iTrader

PM

PM