-

Contributing Member

Wax

He showed three pictures of percussion rifle locks recovered from a New Orleans museum after the big hurricane immersed them in salt water: untreated was a ball of rust, waxed cold had some rust, waxed hot had no rust. It was impressive.

His argument against oil on the wood was that it darkens over time and can't be removed. If you want to preserve it in it's original state for the very long term (like a museum), he said wax is the answer. linseed oil essentially turns into linoleum.

essentially turns into linoleum.

Real men measure once and cut.

-

The Following 2 Members Say Thank You to Bob Seijas For This Useful Post:

-

06-28-2015 10:36 AM

# ADS

Friends and Sponsors

-

FREE MEMBER

NO Posting or PM's Allowed

Well thank yall for the help and information! I'm working on the stocks now. They look good.

-

-

FREE MEMBER

NO Posting or PM's Allowed

untreated was a ball of rust, waxed cold had some rust, waxed hot had no rust. It was impressive.

His argument against oil on the wood was that it darkens over time and can't be removed. If you want to preserve it in it's original state for the very long term (like a museum), he said wax is the answer. Linseed oil essentially turns into linoleum.

Bob, I'm intrigued with the museum curator's experience from Hurricane Katrina -- is there more to add to this?

Also, I have some antique guns that I collected with my father as a kid in the '50s and '60s. We used BLO on them, and they turned chocolate brown in the intervening ~50 years. I'd be interested in your (and others) insights:

on them, and they turned chocolate brown in the intervening ~50 years. I'd be interested in your (and others) insights:

(BTW, I'm not promoting or adhering to the following, just commenting)

1) True, the linseed oil does turn to a form of linoleum (but not exactly the same thing -- BLO is much softer).

is much softer).

2) I've had no problem removing the old BLO (using alcohol or ammonia or paint stripper),

3) There is a nice patina under the wood after the BLO has been removed,

4) Giving wood a good soaking in BLO "feeds" the wood, keeping wood fibers less resistant to rot. Hard-rubbing it all off with a terry-cloth towel, heating the surface with friction seems to make the remaining BLO much "harder" and "drier", with no surface residue, leaving it ready for a Tung Oil treatment.

5) Tung Oil gives a harder, more durable finish than BLO, and doesn't seem to darken with age,

6) I've used wax as a final finish, but never as a sole finish as it is softer (less durable) than Tung Oil.

7) Treating the wood/metal interface with a soft wax substance prevents metal (i.e. barrels and screws, etc. ) from rusting where they contact wood, and protects wood from "oil rot". Enfield Armourers concocted a 50/50 potion of Mineral Jelly & Beeswax and US gunners apparently used Gunny Paste (Linseed, Turpentine, & Beeswax) for this. (I've found candlewax seems to be a decent substitute for beeswax)

8) Never tried the hot wax approach (but would be interested in learning more)

Mates, please chime in with your thoughts -- there's a lot to be learned here. Some people are purists about using the original processes; others are looking 100 years forward for after-effects; and still other's are looking for the "best" durability & aesthetics.

Last edited by Seaspriter; 06-30-2015 at 08:56 AM.

-

FREE MEMBER

NO Posting or PM's Allowed

-

Contributing Member

Feeding

Dave Arnold, the Preservationist, is one of the top men in the field... he was emphatic that "wood is not hungry or thirsty" and does not need "feeding." We wrote up his lecture at the 2005 GCA Convention in the Summer 2006 Journal. He said that if you are trying to duplicate the finish on a modern military arm, go ahead and use it, but it is very bad for long term preservation. If there is a way to link it here, I would provide a copy, it's in pdf format. The article contains the photos of the Katrina locks previously mentioned.

Convention in the Summer 2006 Journal. He said that if you are trying to duplicate the finish on a modern military arm, go ahead and use it, but it is very bad for long term preservation. If there is a way to link it here, I would provide a copy, it's in pdf format. The article contains the photos of the Katrina locks previously mentioned.

Real men measure once and cut.

-

The Following 3 Members Say Thank You to Bob Seijas For This Useful Post:

-

FREE MEMBER

NO Posting or PM's Allowed

Your curator is correct, wood does not "need" feeding, however, it does need protecting with some kind of finish. Raw, unprotected wood will deteriorate and looks awful. Even axe handles get some kind of finish. Soaking wood with raw linseed, or even boiled linseed oil or tung for that matter is not necessary, and certainly not desirable. Careful application of the same oils, however, will result in a decent looking finish that enhances the appearance of the wood and offers a degree of protection from the elements. Once this is achieved wax away till your heart is content for that extra level of ultimate protection. I doubt if even your curator would think of wax as the only finish needed for a stock. I would also be curious how well the wax would stand up to actual field use. It certainly works well for museum pieces.

or tung for that matter is not necessary, and certainly not desirable. Careful application of the same oils, however, will result in a decent looking finish that enhances the appearance of the wood and offers a degree of protection from the elements. Once this is achieved wax away till your heart is content for that extra level of ultimate protection. I doubt if even your curator would think of wax as the only finish needed for a stock. I would also be curious how well the wax would stand up to actual field use. It certainly works well for museum pieces.

-

FREE MEMBER

NO Posting or PM's Allowed

Feeding: Dave Arnold, the Preservationist, is one of the top men in the field... he was emphatic that "wood is not hungry or thirsty" and does not need "feeding." We wrote up his lecture at the 2005

GCA

Convention in the Summer 2006 Journal. He said that if you are trying to duplicate the finish on a modern military arm, go ahead and use it, but it is very bad for long term preservation. If there is a way to link it here, I would provide a copy, it's in pdf format. The article contains the photos of the Katrina locks previously mentioned.

Bob, thank you for the reference to Dave Arnold's article from GCA. Quite interesting. His perspective is from the museum collector, which give a very unique perspective, a set of insights some of which seem universal, and some which, to my mind, are suited for hermetically sealed museum cases. For those interested, I created a download link: (these links work on my computer, if anyone has a problem, let me know.)

http://www.trusting1.com/Museum_Rest...vid_Arnold.pdf

Dave Arnold is a "museum curator" and takes a position that the gun will never be shot in the future. For many of us, both being able to shoot the gun and keeping it in fine condition for the future is important. His insights on humidity are important. For an example, for anyone living in a wooden house, just watch how fast the wood weathers on the south side (exposed to sun & rain = constant expansion & contraction) versus the north side. Every crack in the wood is a place for water, bugs, bacteria, and fungus/mold to start their attack on wood. I kept one gun in a closet where it got no ventilation all summer, and in the fall when I pulled it out, it was covered with white mold -- never will I do that again! (Dark, warm, humid places are ideal breeding grounds for fungi/mold spores, which attack wood mercilessly.)

Also, I have written a piece on historic gun restoration about what I've learned, which applies especially to Enfields, but is applicable to most any military rifle or carbine. (please don't take my word as the Gospel, but just as a reference point for discussion.) It can be downloaded as well:

http://www.trusting1.com/Laws___Prin...ation_V1.2.pdf

I'm always interested in any "discoveries" or proofs of one approach versus another.

Regarding the "Feeding" of wood, I would take the position that wood does need "feeding" especially to keep the bacteria, fungus, and insects out of wood. Wood that is "starved" becomes the breeding ground for all kinds of problems. Having restored old (200 years and older) houses, antique boats (50 years old), and old guns (250 years old), I have had a little experience in this area. Some woods, like teak, have natural oils and toxins that make it very resistant to rot. The sap in pine also retards rot, but doesn't make it rot proof. Walnut contains a natural toxin that retards rot; but many woods used in historic firearms, like maple, birch, and beech, are highly susceptible to rot, which is a destruction of the wood fibre. Rot can be the result of the wood becoming too dry (put it in the sun for a long time and watch the wood fibres break-down), or in the water ( and watch fungi and bacteria eat away at it,) and on and on. That's why we paint or stain exterior woodwork on homes (and oil-based paint is still better than latex) and why we use pine as an exterior wood (because the sap resins resist insects, fungi, and bacteria.) Oils in wood keep the fibres flexible, enabling them to bend when impacted or resist internal cracking when subjected to changes in temperature and humidity. (But over-soaking with too much oil that never dries, such as RLO, is not good either, and gun oil in wood can soften interiors adjacent to receivers, causing compression damage from recoil)

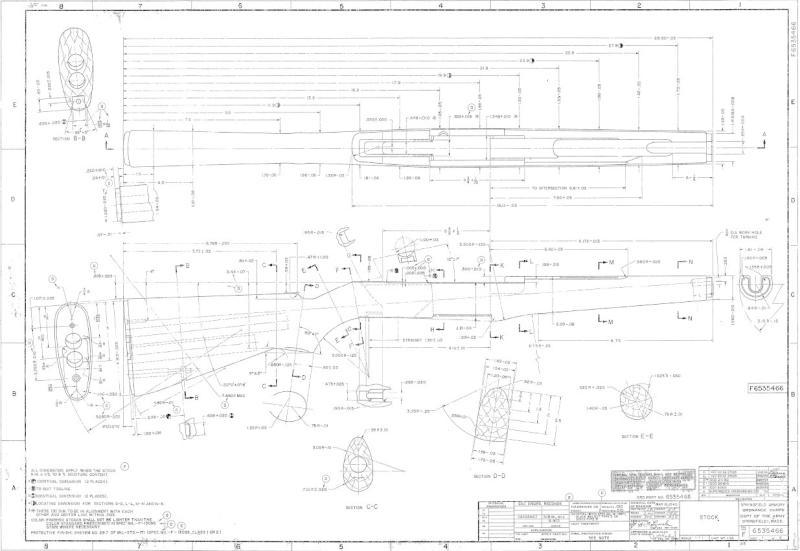

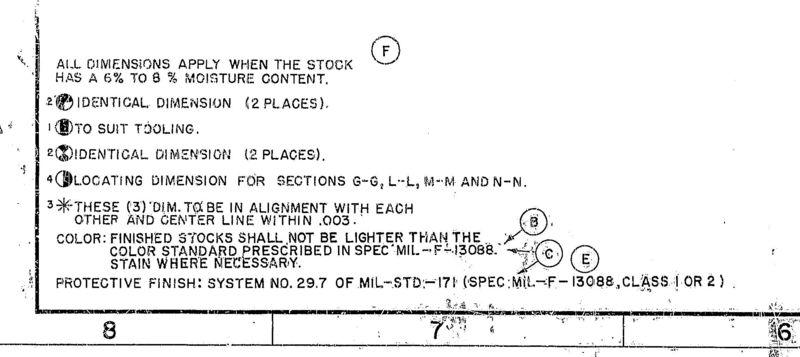

"Feeding" the wood fills hollow wood cells with oils, thus repelling water and helping the wood resist fungus, bacteria, and little insects. Enfields, Springfields, and M-1s were originally dipped in warm linseed oil . Enfields were put in a tank of RLO for 20 hours (see MKL

. Enfields were put in a tank of RLO for 20 hours (see MKL video) RLO was used originally, but later BLO

video) RLO was used originally, but later BLO was found to be better because the molecules "polymerized" -- meaning they became elongated/connected and dried better. M-1s, from what I understand from the CMP

was found to be better because the molecules "polymerized" -- meaning they became elongated/connected and dried better. M-1s, from what I understand from the CMP website, were then treated with Tung Oil, which is a better water repellant and anti-fungal. (Personally, if I was to subject a wooden stocked rifle to combat conditions in a jungle, I'd use one of the deck oils used on wooden boats, which are very water repellant and fungal retardant and durable. But few of us are fighting in the jungles of Southeast Asia anymore, thank God.)

website, were then treated with Tung Oil, which is a better water repellant and anti-fungal. (Personally, if I was to subject a wooden stocked rifle to combat conditions in a jungle, I'd use one of the deck oils used on wooden boats, which are very water repellant and fungal retardant and durable. But few of us are fighting in the jungles of Southeast Asia anymore, thank God.)

As mentioned in earlier posts, the idea of "Enfield Armourer's wax" or "Gunny Paste" to treat areas where gun oil can saturate the wood or wood can interact with metal causing rust is just another approach to 'feeding" wood. The basis of the "gunny paste" formulation goes back at least into the 1800s when beeswax, turpentine, and linseed oil was used as furniture polish.

Anyone who has ever tried to remove an old butt plate screw knows that steel screws can rust from their contact with wood, and be almost impossible to remove. Treating them with the "Enfield Armourer's wax" solves this problem. Enfield Armourer, Captain Laidler , admonishes those who remove the grease from barrels in contact with wood because wood will cause a barrel to pit where it contacts wood, especially in high humidity environments.

, admonishes those who remove the grease from barrels in contact with wood because wood will cause a barrel to pit where it contacts wood, especially in high humidity environments.

The idea of "feeding" wood didn't originate with museums, it came from experience in the field of action -- on the battlefield and on the oceans -- from hard-nosed practionners those who had to survive in harsh and hostile environments. Use of linseed oil on wood stock goes back 100s of years, and I know of no wood that was damaged by this practice, and, to the contrary, I know or have owned many guns and boats that survived because of oil treatment to the wood.

Regarding wax, I am a great fan of wax, especially those that use a combination of beeswax and carnauba wax. Wax is great for preserving metal where the bluing has worn off. On wood, wax should never be used on raw wood -- it gets into the pores and cannot be removed. Wax is best over a good, hardened finish -- such as Tung Oil or varnish. From years of experience I've found it keeps varnish fresh, resistant to oxidation, and cracking.

------ If there is any interest, we can start a new thread just on these issues.

Last edited by Seaspriter; 07-07-2015 at 11:18 AM.

-

FREE MEMBER

NO Posting or PM's Allowed

Thanks everybody for the help and ideas!! I've been working on the wood and it is looking alot better! Thanks again for the help!

-

-

The Following 3 Members Say Thank You to Rick B For This Useful Post:

-

FREE MEMBER

NO Posting or PM's Allowed

Why do you got 5,000 stocks?? Are you selling them?

essentially turns into linoleum.

PM

PM