Looks like you missed the text surrounding that quote from Hatcher -

The point of this post was to clarify that the pressure problems associated with greased bullets are the result of excess grease preventing the neck from expanding to release the bullet cleanly. This is very different from the added bolt thrust we get when lubricant on the case body reduces friction between case and chamber. NOT THE SAME THING! OK?

When contemplating the waxy lubricant band that used to be featured on Swiss7.5 ammunition (GP11), don't overlook the fact that the Swiss chamber features an elongated neck designed to accommodate it.

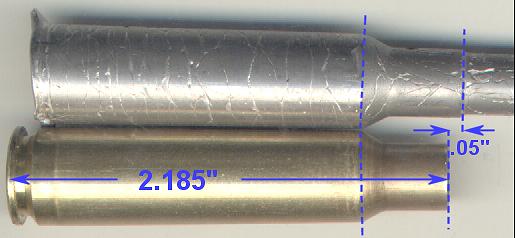

Swiss 7.5 chamber neck is significantly longer than cartridge case, leaving room for lubricant formerly applied during manufacture.

There are practical and "approved" uses for lubed cases. Before the development of the fluted chamber (which allows powder gas to prevent adhesion of case to chamber), it was fairly common for automatic arms to employ lubricated cases or chambers. Most of these were MG's or LMG's, but two well-known shoulder rifles, the US Pedersen .276 and the SwedishAG42 Ljungman are documented as requiring lubricated cases for reliable functioning.

None of this means that lubing your .303 cases and firing them in your Lee-Enfield is a recommended practice. I've been doing it for years with no problems - but I'm a reasonably conservative handloader and my Lee-Enfields are all in sound condition. Some very good people think it's a terrible idea and will damage something sooner or later.

I believe those who assert that radial expansion contributes to the kind of head separation commonly encountered by .303 reloaders are mistaken. Radial expansion puts the circumference of the solid case web in shear, not stretch - and it does so in a completely different location. Failure in this manner is very uncommon with good modern brass and I've never seen an actual example, but here's a lousy picture from an old book that shows what occurs and where -"Longitudinal and radial elongation play a role in creating the stress line that is a prominent feature in the typical Enfield head separations."

- Knowledge Library

- MKL Entry of the Month

- Australia

- Austro-Hungarian Empire

- Canada

- Czechoslovakia

- Denmark

- Finland

- France/Belgium

- Germany

- Italy

- Japan

- Norway

- Russia

- South America

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Turkey

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Yugoslavia

- Is my rifle authentic or a fake?

- Jay Currah's Lee Enfield Web Site

- On-line Service Records (Canada)

- Technical Articles/Research

- Forum

- Classifieds

- What's New?

-

Photo Gallery

- Photo Gallery Options

- Photo Gallery Home

- Search Photo Gallery List

-

Photo Gallery Search

- Video Club

- iTrader

PM

PM